Current nightly builds of KeY contain a new feature called state merging, a technique to decrease the size of proof trees arising from the symbolic execution of large programs.

KeY is primarily a system for heavyweight symbolic execution (mainly of Java programs); programs are executed by a symbolic interpreter based on a set of symbolic execution rules in dynamic logic. Heavyweight symbolic execution is a powerful technique for program proving and other applications, such as symbolic debugging (see our SED tool). However, it suffers from the so-called path explosion problem: Basically, the execution splits into independent branches at each static branching point in the program, which makes it difficult to tackle large programs.

Consider the following program computing the Greatest Common Divisor (GCD) of two integers:

https://gist.github.com/rindPHI/8d7a2415f16599e0b77b01d330f5c811

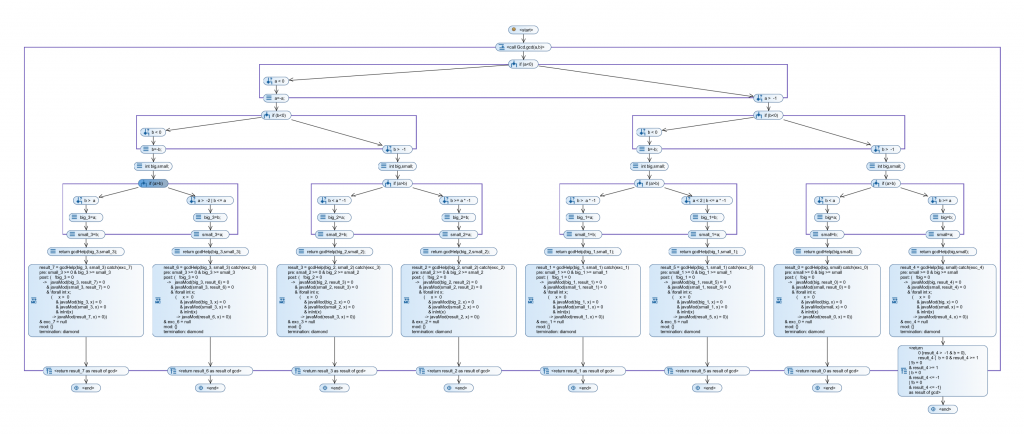

At the beginning, a seemingly harmless normalization takes place: Negative inputs are inverted to positive ones. This is already a problem for symbolic execution, since after line 9, we already have four symmetric branches in the symbolic execution tree:

This is where state merging enters the place. It allows to merge together nodes in the symbolic execution tree which share the same program counter, i.e. the same remaining program to execute. You can use it interactively from within the GUI of KeY, or by adding merge point specifications to your source code. The latter is clearly the recommended way to proceed, since it is more transparent, better to automate and less error-prone. The following code sample shows these annotations within our GCD example:

https://gist.github.com/rindPHI/5765c26f57c35d62f6dbeb11dca57012

The merge_point specification elements (KeY-specific extensions to JML, the Java Modeling Language) indicate where branches should be merged. It can be as easy as writing //@ merge_point; which will merge branches based on a non-parametric “if-then-else” procedure (the merge_proc "MergeByIfThenElse" part is optional since it’s the default). If you want more control, you can use the “Predicate Abstraction” technique as in lines 15-20: We are there interested in the facts that the changed inputs for state merging (the variable b in that case) are positive and either equal the initial value of b or its negative. The conjunctive part says that KeY should check for all conjunctions of the predicates which one holds. That is, from all elements of the power set of predicates we create a conjunction of predicates in the element; here we have two predicates, therefore we end up with three conjunctions, two of which consist of one predicate only. If KeY manages to prove that one of these conjunctions holds for the inputs, then the most specific one is used to abstract away from the actual differing values in the merged states during the merge. Instead of conjunctive, you can also specify that you’re interested in all disjunctions (disjunctive) or in only the single predicates as they are (simple). If none of these so created “abstract elements” holds, then KeY uses a “top” element for abstraction, which basically means that you loose all the knowledge about the differing variables of the merged branches except for the name and type of the variables.

As a general guideline, state merging should be interesting for you if you analyze large programs with lots of splits (a high cyclomatic complexity), or if you have simple splits rather early in your program, as in our “GCD” example. State merging works best if applied most locally; in the example, we could also decide to merge at line 31, which would however increase the proof size substantially due to overly complex expressions in the merged state and a lower potential for savings since there is less code left to execute.

The Gcd example is included in the examples shipped with KeY: In KeY, open “File -> Load example” and navigate to “Getting Started -> State Merging”. For more information, have a look at the following paper, which discusses the theory behind state merging in KeY:

Update: The following journal paper discusses improvements of proof sizes in a case study on the TimSort sorting algorithm, which is part of the Java standard library. Several proofs got significantly shorter by using state merging; the proofs of two methods, which were out of reach without state merging techniques, finally got feasible thanks to this technique.