Summary. Abstract Execution (AE) is a new program analysis technique for automatically proving second-order properties about programs. It is based on the symbolic execution of abstract programs with second-order symbolic stores.

Abrupt completion is analyzed in separate SE branches. AE has been successfully applied to show that almost all statement-based Java refactoring techniques are unsound—unless constrained with suitable preconditions. Assuming these preconditions, we automatically proved the transformations correct. With REFINITY, there is now tool support for using AE for your own problems. Program proving makes it possible to show the correctness of an individual program for all possible inputs. This is a huge advance over testing, as you simply cannot miss the one important input that will make your program crash, and thus your rocket explode, balance of your savings account get negative, or patient die (just to name some classic, “motivating” examples). The reason why not everybody is using program proving (sometimes also called formal (program) verification) is that as of now, formal verification does not scale to large systems.

Formal Verification Does Not Scale

Why is that the case? First, we must not forget that we are talking about difficult, frequently undecidable problems. This means that certain problems cannot be efficiently solved, i.e., are entirely impossible to solve, require human input or simply a huge amount of time and space to be processed. Second, formal verification suffers heavily from the so-called specification bottleneck. To prove a program correct, you first have to define what you actually want to prove, in form of, for instance, a pre- and postcondition; for actually conducting proofs, you will need additional auxiliary specification elements like loop invariants or contracts of (sometimes recursive) helper methods. The automatic generation of such auxiliary specifications is an active research field, but, in the current state, far away from being solved. Even more important: Have you ever used a library method, e.g., a sorting method on a List or a simple “equals” on a String? Then it is quite possible that you no longer can prove your program correct, since there is no specification available for that library (and even if the code base for that library is available, including (i.e., inlining) all that third-party code in you verification process is impractical to infeasible).

Should we give up? Well, of course not!

Should we therefore give up formal verification, understand that testing is our only choice and that we will not be able to use program proving in daily life? Well, of course not (What did you think? You’re reading an article at key-project.org…)! If you are considering sending a rocket to Mars, it can be worth the trouble of verifying the safety-critical core of your control software. Additionally, we can look around and find applications for our methods that are not affected that much of the specification bottleneck. For instance, KeY’s Symbolic Execution Debugger is an example where heavyweight symbolic execution is used in a practical scenario not relying so much on specifications. Furthermore, instead of proving a program correct with respect to a specification (for which you need the specification…), you can prove a program correct with respect to a program. This research field, called Relational Verification (because you prove a relation between two programs, e.g., equivalence) covers such diverse areas as information flow security, (correctness of) compilation, optimization, regression verification and program transformation.

Get More out of Our Methods

Another way to get more out of our methods is to… well, get infinitely more out of them! This article is about a technique called Abstract Execution by which you can prove functional and relational properties not just about one (pair of) program(s), but over an infinite set of programs matching a certain structure, in other words, second-order program properties. Assume that you have a program

if (balance < 0) {

reportOldBalance(balance);

balance = 0;

} else {

reportOldBalance(balance);

balance += bonus;

}

which is doing nothing particularly interesting; still, you take the time to optimize it be factoring out the common statement of the conditional:

reportOldBalance(balance);

if (balance < 0) {

balance = 0;

} else {

balance += bonus;

}

Now, instead of specifying a contract for the program and proving the program before and after the transformation correct (two proofs), you use a relational verification technique and prove equivalence of the two versions with a minimal specification in one proof. Unfortunately, your proof never finishes since the shown code is embedded in a monster method with hundreds of loops and library calls! In an alternative wold, you have a stronger computer, which closes the proof after two days; however, in the meantime your program changed, and you cannot be sure anymore that your proof has any meaning at all.

Wouldn’t it be nicer to not prove the equivalence of those two programs, but that it, in general, is OK to pull out a statement of a conditional (if certain conditions are met; unfortunately, that technique is not correct in general!), and re-use that result every time you apply that transformation?

This is what we understand by second-order properties. What you do, instead of proving equivalence of those two programs, is to prove a relational property over to abstract programs:

if (\abstract_expression boolean e) {

\abstract_statement P;

\abstract_statement Q1;

} else {

\abstract_statement P;

\abstract_statement Q2;

}

\abstract_statement P;

if (\abstract_expression boolean e) {

\abstract_statement Q1;

} else {

\abstract_statement Q2;

}

Abstract Execution: Symbolic Execution of Abstract Programs

“Abstract Execution” (AE) is the symbolic execution of abstract programs, by which we understand programs with abstract statements (like \abstract_statement P;) and abstract expressions (like \abstract_expression boolean e). The technique has first been presented at FM’19 (see reference at the end of this page) and applied to proving the correctness of statement-based refactoring rules. In the meantime, AE has evolved. It is now possible to specify abstract programs with dynamic frames (the locations that a program may read and write are not concrete, like obj.field of x, but abstract specification variables like myFrame or footprintOfQ1) and arbitrary functional postconditions; also, you can specify expressive assumptions about abstract program models, like \disjoint(myFrame,yourFootprint) that are considered by the (abstract) symbolic execution engine of KeY (with AE extension). For instance, the complete model of the abstract program above looks like this:

/*@ ae_constraint \disjoint(frameE, footprintP) &&

@ \disjoint(frameP, footprintE) &&

@ \disjoint(frameP, frameE) &&

@ \disjoint(frameE, relevant) &&

@ \disjoint(frameP, relevant) &&

@ \mutex(throwsExcE(\value(footprintE)),

@ throwsExcP(\value(footprintP)),

@ returnsP(\value(footprintP)));

@*/

{ ; }

if (

/*@ assignable frameE;

@ accessible footprintE;

@ exceptional_behavior requires throwsExcE(\value(footprintE));

@*/

\abstract_expression boolean e

) {

/*@ assignable frameP;

@ accessible footprintP;

@ exceptional_behavior requires throwsExcP(\value(footprintP));

@ return_behavior requires returnsP(\value(footprintP));

@*/

\abstract_statement P;

//@ assignable frameQ1;

//@ accessible footprintQ1;

\abstract_statement Q1;

}

else {

/*@ assignable frameP;

@ accessible footprintP;

@ exceptional_behavior requires throwsExcP(\value(footprintP));

@ return_behavior requires returnsP(\value(footprintP));

@*/

\abstract_statement P;

//@ assignable frameQ2;

//@ accessible footprintQ2;

\abstract_statement Q2;

}

The nice feature is that you can prove the correctness of such a program transformation technique automatically, and obtain a strong and reusable result for an infinite number of programs, namely all those that satisfy the requirements of the abstract model (e.g., \disjoint(frameE,footprintP) states that the guard of the conditional may not change the locations on which the abstract statement P depends. And yes, this is a possible complication, as expressions, such as --x+(z++)>=methodThatChangesTheHeap(--z), may have a number of side effects!). That we can prove such transformations automatically is not a given, considering that we are talking about a second-order property. Such properties are frequently proven in frameworks that require heavy interaction, such as interactive theorem provers like Coq and Isabelle—if they are proven at all!

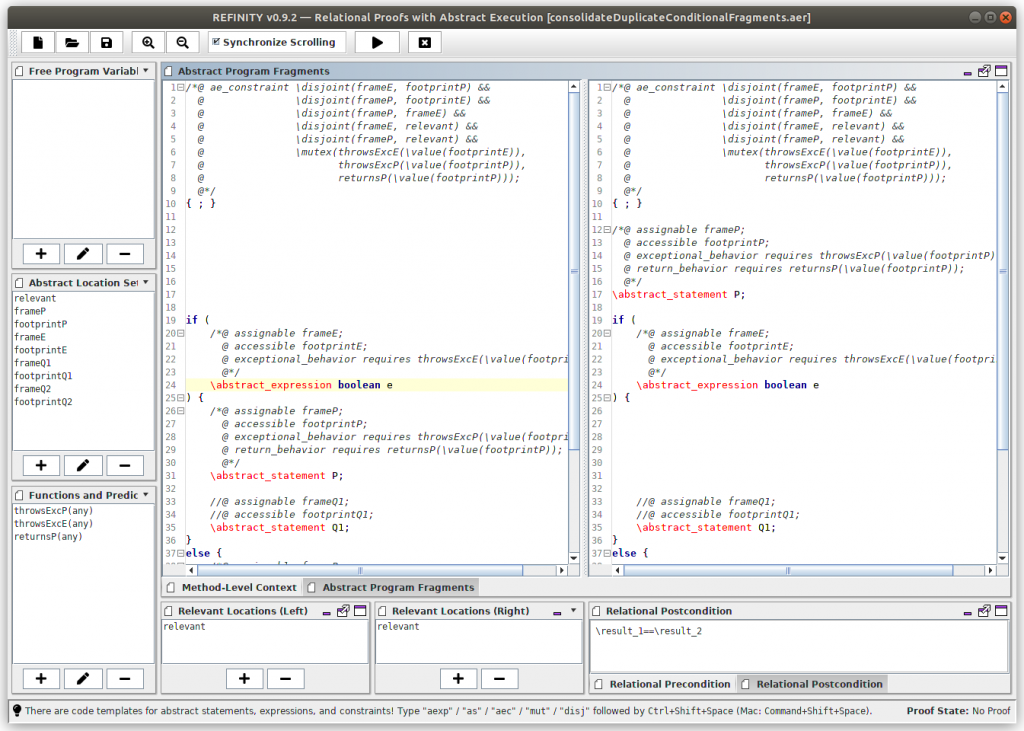

There Exists Tool Support Now: REFINITY

For using Abstract Execution in relational proofs within KeY, there exists tool support now: The tool REFINITY allows to specify two abstract program fragments together with all needed specification variables and a relational pre- and postcondition, and automatically translates this to the general KeY input syntax. If your model is correct, you can prove its correctness in most cases by pushing the “play” button in REFINITY. If it isn’t (and there are so many subtleties in program refactoring, or other transformation techniques…), you can interact with the KeY proof to find the problem.

The Three Pillars of Abstract Execution

Theoretically, Abstract Execution builds on three pillars:

- Second-order state changes based on abstract updates,

- creation of symbols “fresh for” APE identifier symbols, meaning that they are created fresh on the first occurrence of an abstract program element with an identifier symbol P in a proof context, but are re-used every time that an APE with identifier symbol P re-occurs,

- creation of separate SE branches for all reasons of abrupt completion of an abstract program element.

The most important constituents are abstract updates which represent a big number of state changes at once. Concrete updates, like “x := y“, have always been a central part of KeY; with abstract updates “frame, x := z, footprint, o.f“, KeY receives their second-order counterparts.

Abstract Execution can not only be used to prove the correctness of refactoring techniques. There are planned, or ongoing, collaborations with experts from other areas in the directions of

- Correctness-by-Construction

- Cost Analysis

- Program Transformation for Parallelization

…and more is being contemplated! We ourselves thought into the directions of proving the correctness of a rule-based compiler—automatically—which has been the original motivation for Abstract Execution, and to use AE for “lazy symbolic execution” of programs with loops and library calls to mitigate the specification bottleneck. There’s a whole, promising world of second-order program properties out there that are waiting to be proven!

If you are interested in the technique, we invite you to read our paper and to try out REFINITY. The tool ships with a number of examples that hopefully get you started quickly! But never underestimate the many pitfalls that are waiting to bite you when you are transforming your Java program… You’ve been warned.

References

Links